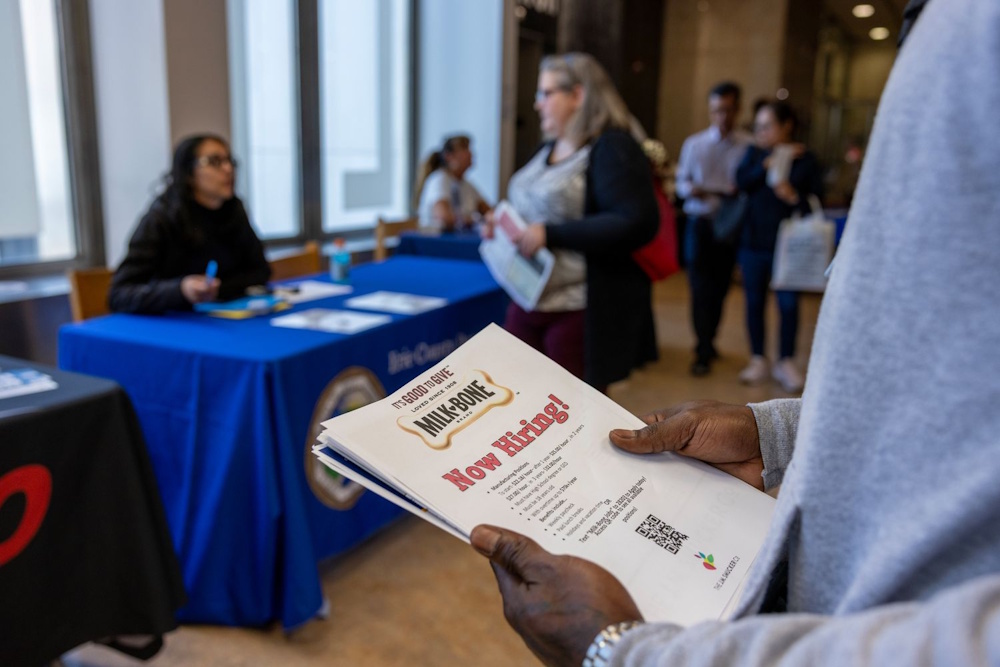

On Wednesday, we will gain initial insights into the condition of the US job market as 2026 commences, alongside a more defined understanding of hiring trends in 2025. The Bureau of Labor Statistics will publish the January jobs report at 8:30 am on Wednesday. The important employment report is experiencing a slight delay due to the recent government shutdown and will indicate whether there has been an improvement in the trajectory of the US labor market, which has been mired in a period of low hiring and low firing activity. In the previous year, the economy recorded its lowest level of job growth outside of a recession since 2003. The year concluded with the economy registering an increase of 50,000 jobs in December, approximately aligning with the average monthly gain observed throughout the year, while the unemployment rate decreased to 4.4%, as reported. “Many workers feel stuck in their careers or feel frozen out of the job market,” stated Daniel Zhao. The critical churn essential for a robust labor market has significantly decelerated, resulting in a greater number of individuals seeking employment than there are positions available. The January jobs report is set to feature a number of significant revisions, particularly the annual benchmark revision, alongside statistical modeling adjustments. These changes will not only offer a more comprehensive perspective on historical employment trends but may also influence our current and future assessments of the labor market.

On Wednesday, a considerable amount of information will be presented, so here is a concise guide to assist in understanding the key points: Anticipate a continuation of the current trends. As we entered this year, analysts projected that monthly job gains might stabilize in the vicinity of 50,000 per month. The latest labor market data, encompassing both public and private sources, suggests a strong probability that job growth was modest, unemployment stayed low, and health care continued to be a key contributor to overall hiring trends. There exists a potential for seasonal and meteorological influences to yield a reading for January that exceeds expectations: Diminished holiday hiring has led to a reduction in post-holiday layoffs, and atypically warm weather in the initial weeks of last month may have supported employment in sectors such as construction. The most recent consensus among economists indicates that job gains for the previous month are projected at 75,000, with the unemployment rate expected to remain steady at 4.4%, as reported. A confluence of factors is at work. On the supply side, the aging and retiring of Baby Boomers, coupled with a slowdown in population growth, has resulted in a significant decrease in immigration and a rise in deportations.

On the demand side, large employers are reducing their workforce after a period of over-hiring during the pandemic. High levels of uncertainty, particularly stemming from the Trump administration’s abrupt and sweeping domestic policy changes, have obscured businesses’ decision-making processes and hindered hiring. Companies have redirected some investments from hiring to equipment and technology, including artificial intelligence, to enhance productivity. Additionally, a high-cost environment, coupled with steep tariffs, reductions in federal funding, and stringent immigration enforcement, has adversely impacted certain businesses. Joe Brusuelas emphasized several factors in response to White House economic adviser Kevin Hassett’s assertion on Monday that the modest job gains are mainly due to declining population figures and increased productivity. “The notion that a deceleration in hiring can be attributed solely to long-term demographic trends is inadequate and serves as a diversion from the real issues surrounding immigration and trade policies – consider the 72,000 reduction in manufacturing jobs last year, which is expected to appear even more severe after the forthcoming benchmark revision,” Brusuelas stated. Federal data is dynamic and often revised as additional detailed and accurate information emerges. The monthly jobs report from the BLS aims to offer a more frequent perspective on employment trends; however, this emphasis on timeliness may compromise accuracy.

The monthly employment snapshot is derived from a survey conducted by the BLS, which engages approximately 121,000 employers across the United States, representing 631,000 work sites and encompassing over a quarter of total employment figures. Respondents are provided with three chances to report their payroll gains and losses for any specific month. Each year, the BLS engages in a methodology designed to deliver a nearly comprehensive employment tally by reconciling the monthly survey estimates with information sourced from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages program, which encompasses approximately 95% of jobs in the United States. The QCEW offers a more thorough and precise assessment of the quantity of businesses, employees, and wages across the nation, as this information is sourced from state unemployment insurance tax records that the majority of employers are mandated to submit. In light of that process, the QCEW exhibits a notable delay: The release of data pertaining to the third quarter of the previous year is scheduled for next month. The preliminary benchmark revision represents an annual initial estimate that aligns with the release of the first-quarter QCEW data. In September, the preliminary revision indicated that the US economy probably added approximately 911,000 fewer jobs than the initial estimates provided in the jobs reports for the 12-month period spanning from April 2024 to March 2025. When distributed, this equates to approximately 76,000 fewer jobs on a monthly basis. If the preliminary estimate were to materialize, it would effectively halve the reported job gains for that period. The process of benchmarking and the substantial revisions to historical employment figures do not constitute evidence of any malicious data manipulation, contrary to the unfounded assertions made by President Donald Trump and others. In reality, they represent the complete antithesis. This process has been undertaken by the BLS in various forms for the past 90 years. These and other revisions illustrate how a transparent and rules-driven organization accounts for and adjusts to new information as it becomes available, according to Groshen and other former officials. If it were to hold – and historical trends indicate that the final revision tends to be smaller – it would represent the largest downward revision on record, according to BLS data dating back to 1979. Analysts anticipate that the ultimate adjustment may result in a downward revision of 700,000 jobs.

This time last year, the final annual benchmarked figure for the 12 months ending in March 2024 was a negative 589,000 jobs seasonally adjusted (negative 598,000 not accounting for seasonality). The final figure is considerably more refined than the initial estimate of negative 818,000 jobs, a number that continues to linger in the collective memory, despite its lack of finality. The final tally of nearly negative 600,000 represents the most significant downward revision since March 2009, which recorded the largest on record at minus 902,000. This revision is also more pronounced than the downward adjustment of 489,000 jobs for the 12-month period ending March 2019, which occurred during Trump’s first term. For context, the adjustments represent a minor fraction (tenths of a percentage point) of total employment. Nevertheless, significant fluctuations, whether upward or downward, generally arise when the economy experiences abrupt changes in volumes that finely calibrated models struggle to detect promptly. The factors likely contributing to the forthcoming downward revision include: declining survey response rates; the BLS’ modeling of business creation, known as the birth-death model, being disrupted by the pandemic and resulting in an overestimation of job gains; and gaps in measurement related to immigration. “This has been a half-decade with enormous changes to the economy – both the pandemic and the beginning and end of the immigration surge,” stated Jed Kolko.

The benchmark revision, which impacts 21 months of non-seasonally adjusted data from April of the previous year through December of the following year, is not the sole adjustment in this forthcoming release. The establishment surveys, by focusing on existing employers, inherently overlook businesses that have recently opened or closed. The Bureau of Labor Statistics developed the “birth-death” model to account for these dynamics. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has refined its birth-death model and will revise historical data generated by the previous model. The agency typically revises its seasonal adjustment models in conjunction with each benchmark revision, which impacts the seasonally adjusted data from the preceding five years.